Jupyter Ecosystem in the Cloud¶

Notebooks are awesome. Perhaps you’ve used them in your classes. But one problem is there are so many. Just at Google we have Colab, Cloud AI Platform Notebooks, and Kaggle Kernels. Several major cloud providers offer Notebook services, and then there are open source efforts like Binder, Jupyter Hub, and a whole ecosystem of tooling. So which should you use? The answer, as usual, is “it depends”. This session will summarize your options and try to help you choose the best notebook services and tools for your needs.

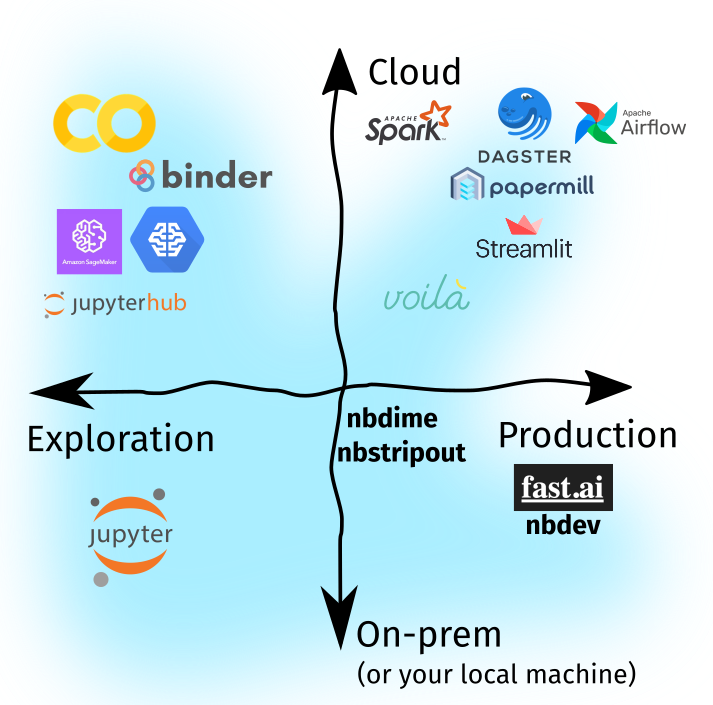

Source: How to use Jupyter Notebooks in 2020 (Part 2 Ecosystem growth)

Contents¶

- Jupyter Ecosystem

- Experiment on the Cloud

- Support for developer workflow

- Quick turnaround from prototype to prod

- Putting-it together

- Principles

- Conclusion

- Footnotes

Jupyter Ecosystem¶

Experiment on the Cloud¶

A huge component of the data science workflow is experimentation. It includes feature engineering, hyperparameter optimization, and testing-out models. As data gets bigger and models get more compute-intensive, it is not enough to do everything on your laptop. Hence, experimentation workloads are often delegated to the Cloud.

Toolbox rundown¶

The figure below shows a collection of tools for cloud-based experiments. I ordered them based on how these services are managed: those further down still requires setup and installation to deploy, while those further up lets you get started immediately. Remember: there’s no perfect tool, just the right one for your use-case. In the proceeding sections, I’ll talk about how I incorporate them in my daily workflow.

| Recommendation | |

|---|---|

| Best Tool of Choice | Google Colaboratory. With Colab, you have immediate access to powerful hardware for your experiments. |

| Runner-up | If you are on a Cloud Platform, I’d recommend checking-out managed notebook instances in AWS Sagemaker or Google Cloud’s AI Platform. |

| Check out | Binder for “publishing” finished work, and JupyterHub if you wish to setup your own managed notebook instances. |

I’d highly-recommend Google Colaboratory as your daily workhorse. It boosts you with the latest hardware (GPUs, TPUs, you name it!) while providing a familiar user-interface. With Colab, you can organize your notebooks in GDrive and share them as to how you’d share any Google Docs or Slides. I’d say that this covers almost 60% of your previous Notebook use-cases.1

The remaining 40% varies: if you’re used to writing Python modules for code reuse, then Colab may feel unwieldy. In addition, Git integration is one-way and idle-time restarts your kernel. You cannot push your own workflow into Colab— you have to do it their way.

Now, if you are using cloud platforms such as Amazon Web Services (AWS) or Google Cloud (GCP), I’d recommend taking a look at Notebook Instances. They are managed Jupyter Notebooks that allows you to customize your machine’s specs. They also have Git integration out-of-the-box, so it’s easy to incorporate any Git repository into the platform. Between the two, I prefer SageMaker notebooks, it’s less buggy and more seamless than Google’s AI Platform Notebooks.

SageMaker and AI Platform Notebooks can be thought of as managed versions of JupyterHub, a multi-user Jupyter infrastructure. I won’t recommend deploying your own Jupyter servers if you’re just working alone— it may be more costly to set-up and maintain. I’d daresay that even if you are in a machine learning research/engineering team and you’re actively using AWS, Azure, or GCP, then just use these services and don’t go through the hassle of spinning-up your own servers.

Lastly, Binder is a tool that I only used once but I see great promise in the future. I used them in Seagull, my Python library for Conway’s Game of Life. There I had some Jupyter Notebook examples that may be better read and interacted with, so I added a “binder launcher” in the README. Try going to my repo’s README, click the “Launch Binder” badge and see the magic happens!

By working in the Cloud and having access to large machines, I was able to boost my productivity and experiment turnaround time. However, moving files from my computer to a remote machine is a hassle. I used to do secure copy, scp, back in grad school (2016), but that too became unwieldy. Upon learning Git and some basic software practices, I was able to optimize my workflow. In the next section, I’d talk about different tools on how to integrate the developer workflow into the Notebook ecosystem.

Support for developer workflow¶

As data science teams grow, we see a confluence of researchers and engineers working together. Unfortunately their toolsets and workstyles vary a lot. Most engineers are comfortable with text editors and IDEs, while some researchers find Jupyter Notebooks convenient. In addition, I’ve met engineers who disdain notebooks, and I’ve met researchers who aren’t familiar with concepts like DRY, 12-Factor, or KISS.2

In an ideal world, everyone uses the same thing and we’re all happy. However in practice, we see (1) engineers supporting the tools comfortable for researchers, and (2) researchers learning basic software engineering principles. This section focuses more on the latter, whereas the next section will concentrate on the former.

Toolbox rundown¶

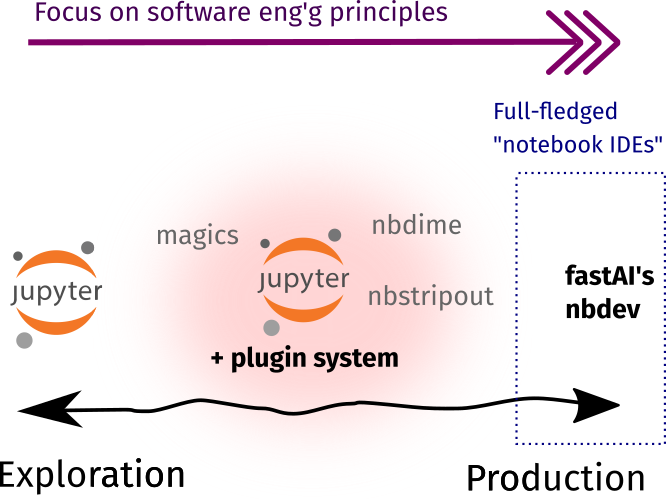

As shown below, most of the tools in this section are already available as Jupyter plugins or extensions. They enable data scientists to practice the developer workflow outside the context of software engineering. There are also some external tools that I included because they work best alongside notebooks!

| In Jupyter-ecosystem | External | |

|---|---|---|

| Best Tool of Choice | nbdime and nbstripout to emulate the Git developer workflow | cookiecutter-datascience to set up a more organized project structure |

| Runner-up | nbconvert to commit your files into a more human-friendly text format | data-version control (DVC) so that you won’t “pollute” your Git repo with model files (can reach GBs) or non-essential doc types (Excel sheets, PDFs, etc.) |

| Check-out | fast.AI’s nbdev as a highly-opinonated way of developing everything in the context of notebooks. |

Native-tooling that resembles the Git workflow and a standardized project-structure will always hit the mark. First, I recommend using cookiecutter -data-science when organizing your data science projects. It definitely works out-of-the-box, and you can configure it the way you like!

One notable thing about their directory structure is that it encourages two things: modularization and documentation. Think of these as the bread-and-butter of software work:

- Modularization means that if you have copy-pasted functions scattered across multiple notebooks, then don’t repeat yourself, and put them in a module where you can define them once and import anywhere.

- Documentation, is the practice of writing text to accompany your analyses and code. My rule-of-thumb is to document aggressively: learn about Python docstrings, Sphinx, and simple Markdown.

Now, Jupyter Notebooks by themselves aren’t suited for a Git-like workflow. Even if they’re just a JSON text file, they become quite unruly when checking for diffs or gulps resolving conflicts. Here, I’d recommend a combination of nbstripout and nbdime.

The command-line tool nbstripout strips the notebook of its output so that it’s easier to parse and compare. Note that even if the code or text inside two notebooks are exactly the same, the output or execution number can still vary—making it harder to diff. I often add nbstripout as a pre-commit hook:

repos:

- repo: https://github.com/kynan/nbstripout

rev: master

hooks:

- id: nbstripout

files: ".ipynb"

Because nbstripout also removes the execution number, it “normalizes” the order of cell execution. As a user, I am now forced to ensure that my notebook will run smoothly from top to bottom. In turn, it is now more seamless for other people to reproduce my notebook since they just need to click “Restart Kernel and Run” and not worry about which cell should run first or what-not.

A perfect pair for nbstripout is nbdime. What I like about it is its content-aware diffing for comparing my teammates’ changes on my notebooks. Yes, you can use their diffs even if you have output cells like images or tables, but I prefer them stripped out. Given these two, my Git experience with notebooks becomes similar to regular source files.

Next, I’d like to talk about nbconvert and DVC because they’re tools that I used once, and would like to revisit again. The command-line tool nbconvert is a good way to convert your Notebooks into Markdown, Python files3, or LaTeX docs. I’ve seen this being used for collaboration, i.e, you convert notebooks (git-ignore) to Python (.py) files before committing them, which allows for easier diffing. Your mileage may vary, but I don’t particularly enjoy this workflow because notebooks aren’t just about code, it’s a collection of tags, metadata, and magic. Instead, I prefer to use nbconvert as a final step of my analysis to transform notebooks into a presentation or a report, where only the cell content matters.

Data version control (DVC) is equally promising—even if we use notebooks or not. I haven’t used it, but its use-case lends itself for more exploration. As of this moment I only store large files (models, huge datasets, etc.) in file-systems such as Amazon S3 or Cloud Storage. Versioning is only done from its descriptive filename (usually YYYYMMDDTHHMMSS-{some_label}). I’m currently exploring this tool, and will probably write about it in the future!

Lastly, I’d like to discuss nbdev. It seems to be an all-in-one solution to use Jupyter Notebooks for everything. I tried this once and there are a few use-cases that I like (and don’t agree) about it:

- For a pure-Notebook exploratory/analysis workflow, nbdev is powerful. An item in my wishlist includes an integrated tool that combines everything to support a developer-like workflow— and nbdev fully-supports that!

- For a software dev’t workflow, I’m a bit skeptical. There’s a feature where you can create Python libraries from your Jupyter Notebook, essentially replacing the text-editor/IDE context for notebook-based development. In my opinion, if data scientists are keen to develop their own libraries, it would be better to onboard them on traditional software engineering dev’t instead.

I feel that nbdev holds a lot of promise, making it a major player in the “Jupyter Notebook IDE” space. I predict that it will be competing against Pycharm’s Notebook Support, or a potential VSCode “Notebook Extension.” I like the push towards Notebook IDEs, as long as they don’t get clunky and heavy.

As tools like these continue to develop, data scientists and researchers can expose themselves to software engineering principles and adopt a developer mindset. Nowadays, a researcher’s output (models, new features, etc.) becomes a software input, thus requiring seamless integration between engineers and researchers. As this section covers how data scientists can learn software principles, the next section focuses on how software engineers can incorporate notebooks into production workloads.

Quick turnaround from prototype to prod¶

The third force of change transforms Jupyter Notebooks from an analysis tool into a software component. This means that an engineer can treat Notebooks as a blackbox with expected inputs and outputs, then run it as she would any other process. In this section, we will look into how notebooks behave as software components and how it integrates with some standard engineering tools.

Toolbox rundown¶

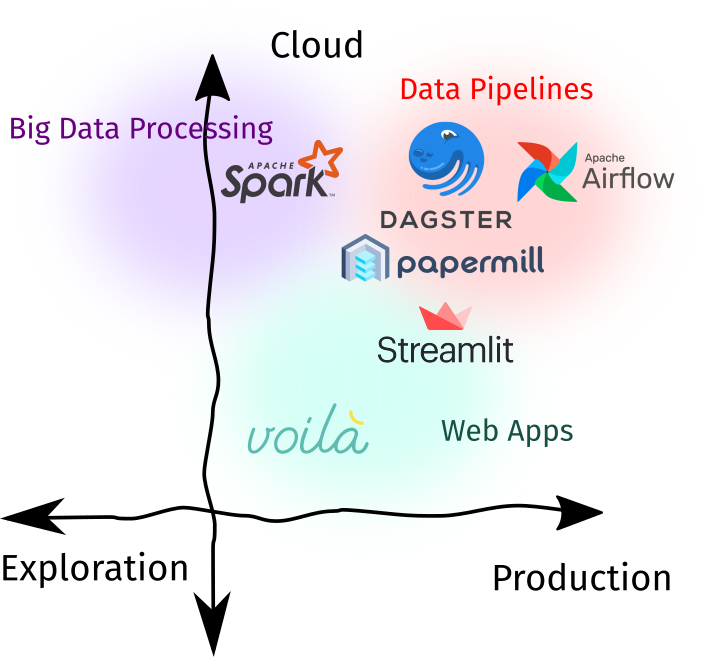

Using notebooks in production is a highly-debated topic. There may be merits in using Notebooks, but it is important for data science teams to evaluate if a Notebook or the standard stack is the right tool for the job. Either way, there exists a plethora of tools that support bringing Notebooks into production. I identify three spaces for this use-case:

- As components of a data pipeline: Notebooks can be thought of as a function that takes in an input, transforms it, and returns an output. For example, it can be used to obtain embeddings from an image before storing it into a distributed filesystem, a final layer in a data pipeline to generate templated reports, or a batch ML service that outputs some predictions for downstream tasks.

- As a web-application: Interactivity is one of the main features of Jupyter Notebooks. On one end you can intersperse code with text, then on the other, you can put widgets for control. Nowadays, there are tools that convert Notebooks into a fully-fledged web application.

- As a big data processing interface: We used to analyze Big Data using SQL, Hive, or some other DSL.4 Nowadays, we can replace this interface with a Notebook-like point-of-contact. This gives enough expressiveness (since we’re using Python) to quickly analye petabyte-scale datasets.

| Recommendation | |

|---|---|

| Best Tool of Choice | Papermill for parametrizing and running notebooks as you’d do for Python scripts. Streamlit, although not Jupyter-native, can be used to create web-apps in-tandem with nbconvert. |

| Runner-up | Voila for a Jupyter-native experience of building web-apps, and Apache Spark for Big Data Analysis. |

| Check out | Dagster (Dagstermill) and Airflow (PapermillOperator) for Notebook-based data pipelines. Although I’d recommend that for critical ETLs, traditional Python scripts should be considered. |

My tools of choice for productionizing notebooks is Papermill. It is a game-changer. In addition, it’s one of the core components of Netflix’s Notebook Innovation blogpost. Papermill allows you to parametrize your notebooks and run them as you would do for any Python script. I’m not Netflix, but I see two advantages of incorporating papermill in one’s workflow: parameterization and mindful analysis.

- With parameterization, I am “forced” to think of the inputs and outputs of my analysis. When modelling, my framework has become like this: “here’s my hypothesis, here are my inputs, and my output is…”. Parameterization also sped-up my experimentation workflow, once I’m done with my papermill-ready Notebook, I just set-up a config file and change it as I wish— pretty convenient!

- In mindful analysis, I slowly think about how to transform my ad-hoc analyses into something that is reproducible. This means that I have to ensure that everytime I press “Restart Kernel and Run All,” nothing would break. It also helps me check which parts of my code can be better off as modularized Python utilities.

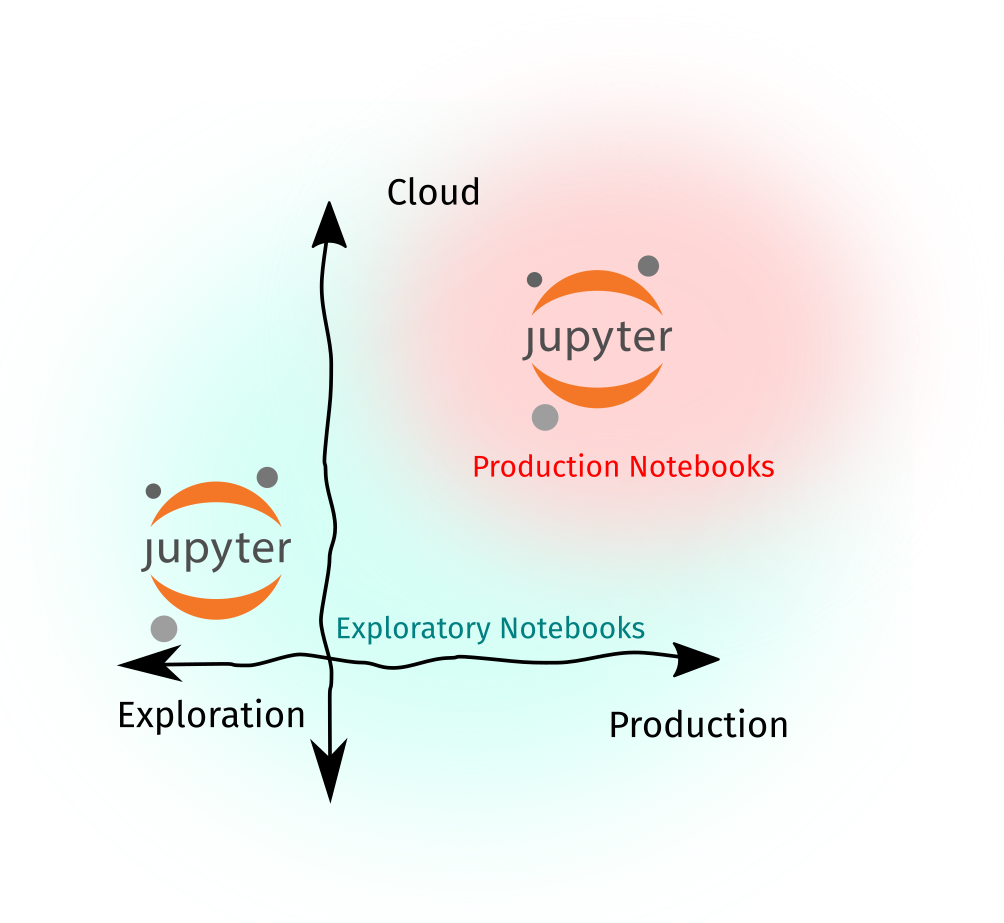

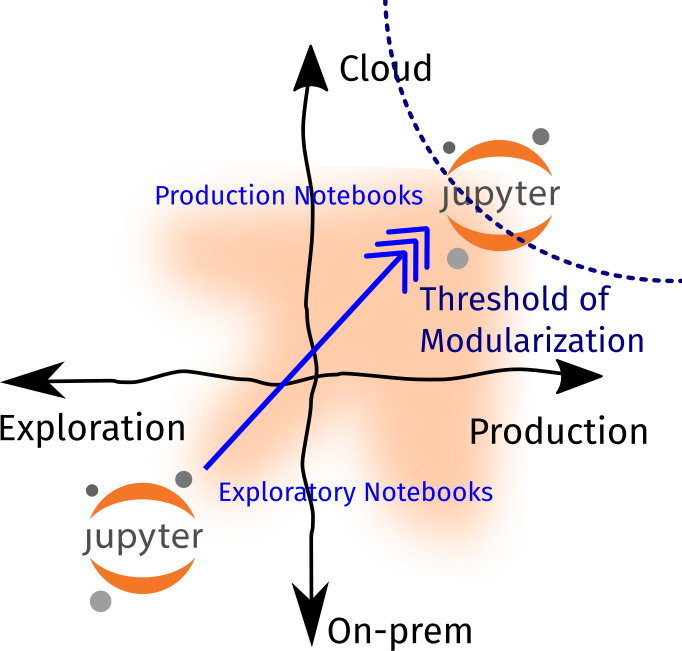

Note that at this stage, we are seeing two types of Notebooks: (1) exploratory notebooks that contain rough or ad-hoc analyses. They don’t have to run perfectly from top-to-bottom, and we don’t use them for downstream tasks—except maybe some output artifacts, and (2) production notebooks that are “papermill-ready,” well-parametrized, and can be readily-inserted in a data pipeline.

Papermill is useful for data scientists if they want to rerun multiple experiments without the lead time of refactoring them into a Python module. For engineers, it abstracts the Notebook into a set of inputs and outputs, while establishing a software contract that says: “Hey, this Notebook will always work and it will always take this and output that.”

The next-stage use-case for Production Notebooks is to chain them together to create an extract-transform-load (ETL) pipeline. Fortunately, staples like Dagster and Airflow support such needs. Both tools, in fact, rely on papermill for notebook execution. However, I highly recommend that for ETL workloads, thorough investigation should be done if a Notebook-based workflow is warranted. In most cases, converting Notebooks into Python scripts can incur less tech debt.

For web-applications, either Streamlit or Voila is the way to go. Voila is Jupyter-native, but Streamlit is attracting its fair share of users. What’s exciting about them is that you don’t need any front-end web dev knowledge to create interactive user interfaces for your models or dashboards. I see this being useful for quick-and-easy presentations where you can showoff your analyses in a more interactive manner than static charts or tables.

Lastly, I’d like to talk about using Notebooks as a primary interface for interacting with big data. The most common example for this is hosting a JupyterHub server connected to a Hadoop Cluster, then accessing data using Pyspark. This gives the advantage of expressiveness since we can use Python to do what we want at-scale. Usually, you’d use an OLAP (Online Analytical Processing) tool like Google Bigquery, Amazon Redshift, or Amazon Athena for these tasks, but a Spark setup can definitely augment your analyses.

Productionizing sofware (even if it involves Notebooks or not), requires understanding the toolset, the common use-cases, and the problem to be solved. In this section, we looked into how we can put Notebooks into production. On the next section, I’d share some of my workflows and principles for Jupyter Notebooks.

Putting-it together¶

As we put things together, I’d talk about some principles and workflows as I work with notebooks. Assuming that I decided to use Jupyter Notebooks for a task, my general principle is this:

Strive to develop your notebooks such that they’re production-ready and can handle large amounts of data at-scale.

This means that even if I start with some ad-hoc and dirty analyses, I always need to update them so that I (or other people) can rerun them seamlessly and understand my methods in the future. To illustrate:

Lastly, I also have a threshold of modularization, where I determine if it’s better to convert my Notebook into a Python script or module. On my end, once I see that my workloads become production and cloud-heavy, then I make the effort to convert my notebooks into a Python script. The goal is to reduce tech debt and increase collaboration.

In addition, the threshold of modularization also reduces the risk for premature optimization (writing scripts early on in the project that may only be used once) and underengineering (using non-maintainable and clunky code to support mission-critical workloads). If you’re in a team, it may be beneficial to determine where this threshold lies so that you have an internal agreement that “it’s OK to use notebooks at this stage but convert them once we’ve reached this scale.”

So how do we ensure that there’s a smooth transition from Exploratory Notebooks to Production ones? Here are some of my workflows / principles:

Principles¶

- Keep a standard project structure and gitflow. I highly-recommend adopting cookiecutter-datascience. By setting a project structure at the very start, you already open the idea for collaboration. Lastly, I encourage that researchers learn gitflow and use some of the tools here to facilitate better collaboration.

- Refactor oft-repeated functions into Python modules. Most of the time, we have functions for loading data, creating charts, or cleaning dataframes that are scattered throughout multiple notebooks. If possible, we can refactor them into Python modules so that we can import them many times. This also helps in turning your exploratory notebooks into production ones in the long-run.

- Ensure that your notebook runs from top-to-bottom. Although Notebooks provide the flexibility to rearrange cells however we want, it becomes a nuisance when the notebook is not ours! This principle requires some discipline: after your analysis, ensure that your notebook runs correctly (doesn’t spit out an error, gives more-or-less the expected results) when clicking “Restart Kernel and Run All.” Once you get past this initial slump, you’re on your way to turning your Notebooks into production-ready onesONnce you get past this initial slump, you’re on your way to turning your Notebooks into production-ready ones.

- For data pipelines, use papermill and configure your notebook to take advantage of it. Papermill is a life-changer. Once I’m done with Principle#3, what I’d do is parametrize my notebooks, create a config file based on these parameters, and rerun these notebooks with the config file as input. It’s so powerful that it can be the bread-and-butter in your project lifecycle from exploration to production!

Conclusion¶

In the second part of the series, we looked deeper into various tools in the Jupyter Ecosystem that contributed (or responded) to the three forces of growth. We started from tools that allow faster and rapid experimentation on the Cloud, tools that support the developer workflow, and lastly, tools that transform notebooks from a vector of analysis into components of production.

We also briefly described the difference between exploratory notebooks and production notebooks, and how we can transition from the former to the latter. Lastly, I discussed about my notebook principle, i.e, to strive to develop notebooks such that they’re production-ready and can handle large amounts of data at-scale. In turn, I introduced the concept of the Threshold of Modularization, which I highly-recommend data teams to consider and set.

In the final part of this series, I’d conclude by looking into how data teams can best leverage notebooks in a technology-management perspective, my wishlist for the Jupyter Notebook ecosystem, and a lookahead into the future of Jupyter Notebooks.

Footnotes¶

-

Generating plots and charts, quick-and-dirty exploratory data analysis (EDA), inspecting a dataset, training models, etc. ↩

-

There’s another breed of data professionals: machine learning engineers (MLE) or research engineers. They’re either researchers who had intermediate (or advanced) software engineering skills or engineers who are venturing into ML/AI. ↩

-

There’s a similar tool, jupytext that solves the same use-case. I won’t be expounding on this since nbconvert seems to work on that space too. ↩

-

This is still a common use-case. For example, Google BigQuery allows us to analyze petabyte-scale data using SQL at “blazing-fast speeds without zero operational overhead.” ↩

Backlinks:

list from [[Jupyter Ecosystem in the Cloud]] AND -"Changelog"